Being an Artist Who Created Sculpture Gardens Public Art Playgrounds Furniture and Stage Sets

| Isamu Noguchi | |

|---|---|

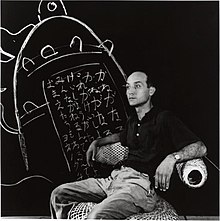

Isamu Noguchi, 1941 | |

| Born | (1904-11-17)November 17, 1904 Los Angeles, California, U.s.a. |

| Died | December xxx, 1988(1988-12-30) (aged 84) New York City, United states of america |

| Education | Columbia University |

| Known for | Sculpture landscape architecture piece of furniture design |

| Notable work | Red Cube (New York City) Black Lord's day (Seattle) Sky Gate (Honolulu) Akari lanterns Herman Miller lounge table Sapporo Moerenuma Park |

| Movement | Biomorphism |

| Spouse(s) | Yoshiko Yamaguchi (g. 1951; div. 1957) |

| Awards | Logan Medal of the arts (Art Establish of Chicago)1963; Gilded Medal, Architectural League of New York1965; Brandeis Creative Arts Award, 1966; Gilded Medal (American Academy of Arts and Messages), 1977; Order of the Sacred Treasure; National Medal of Arts (1987) |

The Garden of Peace, UNESCO headquarters, Paris. Donated past the Regime of Japan, this garden was designed by Isamu Noguchi in 1958 and installed by Japanese gardener Toemon Sano.

Isamu Noguchi ( 野口 勇 , Noguchi Isamu , November 17, 1904 – December xxx, 1988) was an American artist and mural architect whose artistic career spanned half-dozen decades, from the 1920s onward.[2] Known for his sculpture and public artworks, Noguchi likewise designed stage sets for various Martha Graham productions, and several mass-produced lamps and furniture pieces, some of which are still manufactured and sold.

In 1947, Noguchi began a collaboration with the Herman Miller company, when he joined with George Nelson, Paul László and Charles Eames to produce a catalog containing what is frequently considered to be the most influential body of modernistic piece of furniture e'er produced, including the iconic Noguchi table which remains in product today.[iii] His work lives on around the world and at the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum in New York City.

Biography [edit]

Early life (1904–1922) [edit]

Isamu Noguchi was built-in in Los Angeles, the son of Yone Noguchi, a Japanese poet who was acclaimed in the Usa, and Léonie Gilmour, an American writer who edited much of Noguchi's work.

Yone had ended his human relationship with Gilmour earlier that yr and planned to marry The Washington Post reporter Ethel Armes. Afterward proposing to Armes, Yone left for Japan in belatedly Baronial, settling in Tokyo and pending her inflow; their engagement fell through months afterwards when Armes learned of Léonie and her newborn son.[1]

In 1906, Yone invited Léonie to come to Tokyo with their son. She at first refused, but growing anti-Japanese sentiment following the Russo-Japanese War eventually convinced her to take upwards Yone's offering.[4] The two departed from San Francisco in March 1907, arriving in Yokohama to meet Yone. Upon arrival, their son was finally given the name Isamu ( 勇 , "backbone"). However, Yone had married a Japanese woman by the time they arrived, and was by and large absent-minded from his son's childhood. After again separating from Yone, Léonie and Isamu moved several times throughout Japan.

In 1912, while the ii were living in Chigasaki, Isamu's half-sister, pioneer of the American Mod Dance movement Ailes Gilmour, was born to Léonie and an unknown Japanese father. Here, Léonie had a house built for the iii of them, a project that she had the 8-year-old Isamu "oversee". Nurturing her son's artistic ability, she put him in charge of their garden and apprenticed him to a local carpenter.[5] Withal, they moved in one case once more in December 1917 to an English language-speaking customs in Yokohama.

In 1918, Noguchi was sent dorsum to the US for schooling in Rolling Prairie, Indiana. Afterwards graduation, he left with Dr. Edward Rumely to LaPorte, where he found boarding with a Swedenborgian pastor, Samuel Mack. Noguchi began attending La Porte High School, graduating in 1922. During this period of his life, he was known by the name "Sam Gilmour".[half dozen]

Early artistic career (1922–1927) [edit]

After high school, Noguchi explained his desire to become an creative person to Rumely;[7] though he preferred that Noguchi get a doctor, he acknowledged Noguchi'south request and sent him to Connecticut to work as an apprentice to his friend Gutzon Borglum. Best known every bit the creator of Mount Rushmore National Memorial, Borglum was at the fourth dimension working on the group called Wars of America for the city of Newark, New Jersey, a piece that includes forty-two figures and ii equestrian sculptures. Every bit i of Borglum's apprentices, Noguchi received little training as a sculptor; his tasks included arranging the horses and modeling for the monument equally General Sherman. He did, withal, choice upwardly some skills in casting from Borglum's Italian assistants, later fashioning a bust of Abraham Lincoln.[viii] At summer'due south terminate, Borglum told Noguchi that he would never become a sculptor, prompting him to reconsider Rumely'due south prior proffer.[9]

He and then traveled to New York City, reuniting with the Rumely family at their new residence, and with Dr. Rumely's fiscal assist enrolled in February 1922 as a premedical pupil at Columbia University.[ten] Presently later on, he met the bacteriologist Hideyo Noguchi, who urged him to reconsider fine art, too as the Japanese dancer Michio Itō, whose celebrity status later helped Noguchi detect acquaintances in the art world.[11] Another influence was his mother, who in 1923 moved from Nippon to California, and then afterward to New York.

In 1924, while still enrolled at Columbia, Noguchi followed his mother'due south advice to accept night classes at the Leonardo da Vinci Art School. The school's head, Onorio Ruotolo, was immediately impressed by Noguchi's work. Merely iii months later, Noguchi held his first showroom, a selection of plaster and terracotta works. He soon dropped out of Columbia University to pursue sculpture full-time, changing his proper name from Gilmour (the surname he had used for years) to Noguchi.

Subsequently moving into his own studio, Noguchi found work through commissions for portrait busts, he won the Logan Medal of the Arts. During this time, he frequented avant garde shows at the galleries of such modernists equally Alfred Stieglitz and J. B. Neuman, and took a particular interest in a show of the works of Romanian-born sculptor Constantin Brâncuși.[12]

In late 1926, Noguchi practical for a Guggenheim Fellowship. In his letter of application, he proposed to study rock and wood cut and to gain "a better agreement of the homo effigy" in Paris for a twelvemonth, then spend some other year traveling through Asia, showroom his work, and return to New York.[13] He was awarded the grant despite beingness three years short of the age requirement.

Early travels (1927–1937) [edit]

Noguchi arrived in Paris in Apr 1927 and shortly afterward met the American author Robert McAlmon, who brought him to Constantin Brâncuși's studio for an introduction. Despite a language barrier between the 2 artists (Noguchi barely spoke French, and Brâncuși did non speak English[14]), Noguchi was taken in as Brâncuși's assistant for the next seven months. During this time, Noguchi gained his ground in stone sculpture, a medium with which he was unacquainted, though he would subsequently admit that one of Brâncuși's greatest teachings was to appreciate "the value of the moment".[xv] Meanwhile, Noguchi establish himself in good company in France, with letters of introduction from Michio Itō helping him to come across such artists as Jules Pascin and Alexander Calder, who lived in the studio of Arno Breker. They became friends and Breker did a bronze bust of Noguchi.

Noguchi only produced i sculpture – his marble Sphere Section – in his showtime year, but during his second year he stayed in Paris and continued his training in stoneworking with the Italian sculptor Mateo Hernandes, producing over twenty more than abstractions of woods, stone and canvas metal. Noguchi's next major destination was to be India, from which he would travel east; he arrived in London to read up on Oriental Sculpture, but was denied the extension to the Guggenheim Fellowship he needed.

In February 1929, he left for New York City. Brâncuși had recommended that Noguchi visit Romany Marie'south café in Greenwich Village.[16] Noguchi did so and in that location met Buckminster Fuller, with whom he collaborated on several projects,[17] [18] [xix] [20] including the modeling of Fuller's Dymaxion motorcar.[21]

Upon his return, Noguchi'south abstract sculptures made in Paris were exhibited in his first one-homo prove at the Eugene Schoen Gallery. After none of his works sold, Noguchi altogether abandoned abstruse art for portrait busts in order to support himself. He soon found himself accepting commissions from wealthy and celebrity clients. A 1930 showroom of several busts, including those of Martha Graham and Buckminster Fuller, garnered positive reviews,[22] and after less than a year of portrait sculpture, Noguchi had earned enough money to go on his trip to Asia.

Noguchi left for Paris in April 1930, and two months later received his visa to ride the Trans-Siberian Railway. He opted to visit Nippon first rather than Republic of india, but subsequently learning that his father Yone did not want his son to visit using his surname, a shaken Noguchi instead departed for Beijing. In China, he studied brush painting with Qi Baishi, staying for half-dozen months before finally sailing for Japan.[23] Fifty-fifty before his inflow in Kobe, Japanese newspapers had picked up on Noguchi's supposed reunion with his father; though he denied that this was the reason for his visit, the two did run into in Tokyo. He subsequently arrived in Kyoto to study pottery with Uno Jinmatsu. Hither he took note of local Zen gardens and haniwa, clay funerary figures of the Kofun period which inspired his terracotta The Queen.

Noguchi returned to New York amidst the Great Depression, finding few clients for his portrait busts. Instead, he hoped to sell his newly produced sculptures and brush paintings from Asia. Though very few sold, Noguchi regarded this 1-human exhibition (which began in February 1932 and toured Chicago, the west coast, and Honolulu) as his "almost successful".[24] Additionally, his next attempt to pause into abstract art, a large streamlined figure of dancer Ruth Page entitled Miss Expanding Universe, was poorly received.[25] In January 1933 he worked in Chicago with Santiago Martínez Delgado on a mural for Chicago'southward Century of Progress Exposition, and then again found a business for his portrait busts; he moved to London in June hoping to observe more work, but returned in December only before his mother Leonie's decease.

Offset in February 1934, Noguchi began submitting his first designs for public spaces and monuments to the Public Works of Art Program. 1 such design, a monument to Benjamin Franklin, remained unrealized for decades. Some other design, a gigantic pyramidal earthwork entitled Monument to the American Turn, was similarly rejected, and his "sculptural landscape" of a playground, Play Mount, was personally rejected by Parks Commissioner Robert Moses. He was somewhen dropped from the program, and over again supported himself past sculpting portrait busts. In early 1935, later on another solo exhibition, the New York Sun'south Henry McBride labeled Noguchi'southward Death, depicting a lynched African-American, as "a little Japanese mistake".[26] That same yr he produced the set for Frontier, the first of many set designs for Martha Graham.

Subsequently the Federal Art Project started upwards, Noguchi again put forth designs, 1 of which was another earthwork chosen for the New York Urban center airdrome entitled Relief Seen from the Sky; following farther rejection, Noguchi left for Hollywood, where he again worked every bit a portrait sculptor to earn money for a sojourn in Mexico. Here, Noguchi was chosen to pattern his showtime public work, a relief landscape for the Abelardo Rodriguez market place in United mexican states Metropolis. The 20-meter-long History as Seen from United mexican states in 1936 was hugely political and socially conscious, featuring such modern symbols as the Nazi swastika, a hammer and sickle, and the equation E =mc². Noguchi besides met Frida Kahlo during this time and had a brief but passionate affair with her; they remained friends until her death.[27]

Further career in the United States (1937–1948) [edit]

Noguchi returned to New York in 1937. He designed the Zenith Radio Nurse, the iconic original baby monitor at present held in many museum collections. The Radio Nurse was Noguchi's get-go major design commission and he chosen it "my only strictly industrial design".[28]

He once again began to plow out portrait busts, and afterwards diverse proposals was selected for two sculptures. The first of these, a fountain built of car parts for the Ford Motor Company's showroom at the 1939 New York World's Fair, was thought of poorly past critics and Noguchi akin[29] [xxx] but withal introduced him to fountain-structure and magnesite. Conversely, his second sculpture, a nine-ton stainless steel bas-relief entitled News, was unveiled over the entrance to the Associated Printing building at the Rockefeller Heart in Apr 1940 to much praise.[31] Post-obit farther rejections of his playground designs, Noguchi left on a cross-country road trip with Arshile Gorky and Gorky's fiancée in July 1941, somewhen separating from them to become to Hollywood.

Post-obit the attack on Pearl Harbor, anti-Japanese sentiment was energized in the The states, and in response Noguchi formed "Nisei Writers and Artists for Republic". Noguchi and other group leaders wrote to influential officials, including the congressional committee headed by Representative John H. Tolan, hoping to halt the internment of Japanese Americans; Noguchi afterwards attended the hearings but had niggling effect on their outcome. He later helped organize a documentary of the internment, but left California before its release; equally a legal resident of New York, he was allowed to return home. He hoped to bear witness Japanese-American loyalty by somehow helping the war attempt, just when other governmental departments turned him down, Noguchi met with John Collier, head of the Office of Indian Affairs, who persuaded him to travel to the internment camp located on an Indian reservation in Poston, Arizona, to promote craft and customs.[32]

Noguchi arrived at the Poston camp in May 1942, becoming its merely voluntary internee.[32] Noguchi showtime worked in a carpentry shop, just his hope was to design parks and recreational areas inside the campsite. Although he created several plans at Poston, amidst them designs for baseball fields, pond pools, and a cemetery,[33] he institute that the War Relocation Authority had no intention of implementing them. To the WRA camp administrators he was a troublesome interloper from the Bureau of Indian Diplomacy, and to the internees he was an agent of the camp administration.[34] Many did not trust him and saw him equally a spy. He had found nothing in common with the Nisei, who regarded him as a strange outsider.

In June, Noguchi applied for release, just intelligence officers labeled him as a "suspicious person" due to his involvement in "Nisei Writers and Artists for Commonwealth". He was finally granted a calendar month-long furlough on November 12, simply never returned; though he was granted a permanent exit afterward, he soon afterward received a displacement order. The Federal Bureau of Investigation, accusing him of espionage, launched into a full investigation of Noguchi which ended only through the American Civil Liberties Matrimony's intervention.[35] Noguchi would later retell his wartime experiences in the British World War II television receiver documentary series The Earth at State of war.

Upon his return to New York, Noguchi took a new studio in Greenwich Village. Throughout the 1940s, Noguchi's sculpture drew from the ongoing surrealist movement; these works include not merely various mixed-media constructions and landscape reliefs, but lunars – self-illuminating reliefs – and a series of biomorphic sculptures made of interlocking slabs. The almost famous of these assembled-slab works, Kouros, was outset shown in a September 1946 exhibition, helping to cement his identify in the New York art scene.[36]

In 1947 he began a relationship with Herman Miller of Zeeland, Michigan. This relationship was to prove very fruitful, resulting in several designs that take become symbols of the modernist style, including the iconic Noguchi table, which remains in product today. Noguchi also developed a relationship with Knoll, designing furniture and lamps. During this catamenia he continued his involvement with theater, designing sets for Martha Graham's Appalachian Leap and John Muzzle and Merce Cunningham'due south production of The Seasons. Most the end of his fourth dimension in New York, he also constitute more work designing public spaces, including a committee for the ceilings of the Time-Life headquarters.

In March 1949, Noguchi had his first 1-person show in New York since 1935 at the Charles Egan Gallery.[37] In September 2003, The Pace Gallery held an exhibition of Noguchi's work at their 57th Street gallery. The exhibition, entitled 33 MacDougal Aisle: The Interlocking Sculpture of Isamu Noguchi, featured eleven of the artist's interlocking sculptures. This was the get-go exhibition to illustrate the historical significance of the relationship betwixt MacDougal Aisle and Isamu Noguchi's sculptural work.[38]

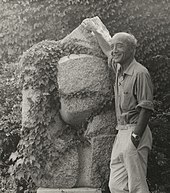

David Finn, Isamu Noguchi at the Noguchi Garden Museum, c.1985, ©David Finn Archive, Department of Image Collections, National Gallery of Fine art Library, Washington, DC

Bollingen Fellowship and life in Japan (1948–1952) [edit]

| | This section needs expansion. You tin can help by calculation to it. (January 2022) |

Following the suicide of his creative person friend Arshile Gorky in 1948, and a failed romantic relationship with Nayantara Pandit (the niece of Indian nationalist Jawaharlal Nehru), Noguchi applied for a Bollingen Fellowship to travel the world, proposing to report public space as research for a volume most the "environs of leisure".

Afterward years (1952–1988) [edit]

| | This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2022) |

In his later years Noguchi gained in prominence and acclaim, installing his large-calibration works in many of the world's major cities.

He was briefly married to the ethnic-Japanese icon of Chinese song and cinema Yoshiko Yamaguchi, between 1952 and 1957.[39] : 115 [forty] : 131, 148 [2]

In 1955, he designed the sets and costumes for a controversial theatre production of King Lear starring John Gielgud.[41]

In 1962, he was elected to membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters.[42]

In 1971, he was elected a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[43]

In 1986, he represented the United states of america at the Venice Biennale, showing a number of his Akari light sculptures.[44]

In 1987, he was awarded the National Medal of Arts.

Isamu Noguchi died on December 30, 1988 at the age of 84. In its obituary for Noguchi, The New York Times called him "a versatile and prolific sculptor whose earthy stones and meditative gardens bridging East and West have become landmarks of 20th-century art".[2]

Notable works [edit]

Heimar (1968), at the Billy Rose Sculpture Garden, State of israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel

- Martha Graham (1929), Honolulu Museum of Art, Honolulu, Hawaii[45]

- Tsuneko-san (1931), Honolulu Museum of Art

- Lunar Landscape (1943–44), now at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art[46] [47]

- Coffee Tabular array (1944), designed this iconic item of Mid-century Modern furniture[48]

- Texas Sculpture (1960–1961), First National Bank of Fort Worth Plaza, Fort Worth, Texas[49]

- Decorative railings for a bridge in Peace Park (1951–1952), Hiroshima, Japan[50]

- 666 Fifth Avenue Ceiling and Waterfall, also known as Landscape of the Cloud (1956–1958), formerly in the lobby of 666 Fifth Artery, New York Metropolis[51]

- Gardens for UNESCO, UNESCO Headquarters (1956–1958), Paris, France[52]

- Floor Frame (1962), The White Firm Rose Garden, Washington, DC[53]

- The Cry (1962), Albright–Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York

- Sun (1963), The Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller Empire State Plaza Art Collection, Albany, New York[54]

- Sunken Garden for Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library (1960–1964), Yale University, New Oasis, Connecticut[55] [56]

- Sunken Garden for Chase Manhattan Bank Plaza (1961–1964), New York City[57]

- Gardens for IBM Headquarters (1964), Armonk, New York[58]

- Billy Rose Sculpture Garden (1960–1965), Israel Museum, Jerusalem[59]

- Children'due south Land (1965–1966), a temporary children's playground for Kodomo no Kuni, Yokohama, Japan[sixty]

- Red Cube (1968), HSBC Building, New York City

- Octetra (1968), Crystal Bridges Museum of American Fine art. It was beginning located near Spoleto Cathedral[61] It is an abstract painted concrete sculpture.[62]

- Untitled Red (1965–66), Honolulu Museum of Art

- Sky Viewing Sculpture (1969), Western Washington University Public Sculpture Collection, Bellingham, Washington

- Black Sun (1969), Volunteer Park, Seattle, Washington

- Expo 'seventy Fountains, Osaka, Japan[63]

- Twin Sculptures, Bayerische Vereins Bank, Munich (1970–1972), Munich, Frg[64]

- Playscapes, Piedmont Park, Atlanta, Georgia (1975–1976), a children'southward playground in Atlanta, Georgia

- Intetra (1976), Society of the 4 Arts, Palm Embankment, Florida

- Portal (1976), Justice Heart Complex, Cleveland, Ohio

- Sky Gate (1976–1977), Honolulu Hale, Honolulu, Hawaii

- Dodge Fountain (1972–1979) and Philip A. Hart Plaza in Detroit, Michigan (created in collaboration with Shoji Sadao)

- Untitled (1981), obsidian and wood sculpture, Honolulu Museum of Art

- Noguchi Garden: California Scenario and Spirit of the Lima Bean (1980–1982), Costa Mesa, California[65]

- Commodities of Lightning...A Memorial to Benjamin Franklin (conceived 1933, installed 1984), Franklin Foursquare, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Constellation for Louis Kahn (1983), Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

- Lillie and Hugh Roy Cullen Sculpture Garden (1986) for the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas

- Bayfront Park (1980–1996), Miami, Florida

- Moerenuma Park (2004), Sapporo, Japan

His final projection was the design for Moerenuma Park, a 400-acre (160 ha) park in Sapporo, Nihon. Designed in 1988 shortly before his decease, it was completed and opened to the public in 2004.

Gallery [edit]

-

Zwillingsplastik Munich

Honors [edit]

Noguchi received the Edward MacDowell Medal for Outstanding Lifetime Contribution to the Arts in 1982; the National Medal of Arts in 1987; and the Guild of the Sacred Treasure from the Japanese authorities in 1988.[66]

In 2004, the United states of america Postal Service issued a 37-cent stamp honoring Noguchi.[67]

Legacy [edit]

Archway to Noguchi Museum, New York City

The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum is devoted to the preservation, documentation, presentation, and interpretation of the work of Isamu Noguchi. It is supported by a variety of public and individual funding bodies.[68] The Us copyright representative for the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum is the Artists Rights Society.[69] In 2012, information technology was appear that, in guild to reduce liability, Noguchi'south catalogue raisonné would be published as an online-just, ever-modifiable work-in-progress.[70] [71]

Exhibition

Grand+ [one] in partnership with the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum organized an exhibition of Isamu Noguchi and Danh Vō. Noguchi for Danh Vo: Counterpoint(Nov 16, 2018 - April 22, 2019) The exhibition have place in the M+ Pavilion, Hong Kong.

See also [edit]

- Wabi-sabi

- Japanese in New York City

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b "Chronology". The Noguchi Museum . Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ a b c Brenson, Michael (December 31, 1988). "Isamu Noguchi, the Sculptor, Dies at 84". The New York Times . Retrieved Jan 2, 2022.

- ^ Pina, Leslie (1998). Archetype Herman Miller. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing. ISBN0-7643-0471-2.

- ^ Duus, 2004. pp. 45–46

- ^ Duus, 2004. pp. 73–74

- ^ Winther, Bert (Fall 1995). "Isamu Noguchi". Art Periodical. 54 (iii): 113–115. doi:ten.2307/777614. JSTOR 777614.

- ^ Noguchi, 1968. p. 14

- ^ Noguchi, 1968. pp. 14–xv

- ^ Noguchi, 1968. p. 15

- ^ "The Abstract Sculptor Who Melded East and Due west". Columbia College Today. Fall 2020. Retrieved Nov 12, 2020.

- ^ "Interview with Isamu Noguchi. Nov 7, 1973.". Cummings, Paul. Retrieved October 19, 2006.

- ^ Noguchi, 1968. p. 16

- ^ "Proposal to the Guggenheim Foundation (1927)". The Noguchi Museum. Retrieved October 18, 2006. Archived Oct 3, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Duus, 2004. p. 114

- ^ Kuh, 1962. p. 173

- ^ Robert Schulman. Romany Marie: The Queen of Greenwich Village (pp. 109–110). Louisville: Butler Books, 2006. ISBN i-884532-74-viii.

- ^ "Interview with Isamu Noguchi". Conducted November 7, 1973 past Paul Cummings at Noguchi's studio in Long Island Urban center, Queens. Smithsonian Archives of American Art.

- ^ Grace Glueck (May 19, 2006). "The Architect and the Sculptor: A Friendship of Ideas". The New York Times.

- ^ John Haber. "Before Buckyballs". Review of Noguchi Museum's All-time of Friends exhibition (2006).

- ^ John Haskell. "Buckminster Fuller and Isamu Noguchi". Kraine Gallery Bar Lit, Fall 2007. Archived from the original on May 13, 2008.

- ^ Michael John Gorman (March 12, 2002). "Passenger Files: Isamo Noguchi, 1904–1988". Towards a cultural history of Buckminster Fuller's Dymaxion Car. Stanford Humanities Lab. Archived from the original on September xvi, 2007. Includes images

- ^ Jewell, Edward Allen (February 9, 1930). "Work by 6 Japanese Artists", The New York Times.

- ^ Isamu Noguchi and Qi Baishi: Beijing 1930, Frye Art Museum (Seattle). Web page for exhibit February 22 – May 25, 2014. Retrieved May 11, 2014.

- ^ Duus, 2004. p. 137

- ^ Duus, 2004. p. 140

- ^ Noguchi, 1968. pp. 22–23

- ^ PBS—The Life and Times of Frida Kahlo

- ^ Banham, Joanna (1997). Encyclopedia of Interior Blueprint. Routledge. ISBN978-1-136-78757-vii.

- ^ Duus, 2004. p. 159

- ^ Noguchi, 1968. p. 24

- ^ "Stainless Sculpture", (May v, 1940). The New York Times. p. 2.

- ^ a b Duus, 2004. p. 169

- ^ Duus, 2004. p. 170

- ^ Duus, Masayo (2004). The Life of Isamu Noguchi . Princeton University Press. pp. 171–172.

- ^ Duus, 2004. pp. 184–185

- ^ Duus, 2004. p. 191

- ^ Noguchi Museum: Timeline (Drag to twelvemonth, then month)

- ^ 33 MacDougal Aisle: The Interlocking Sculpture of Isamu Noguchi Official media release by PaceWildenstein, New York, c. September 2003 (undated) Archived July 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Altshuler, Bruce (1994). Isamu Noguchi (1st ed.). New York: Abbeville Press. ISBN1-55859-755-7.

- ^ Ashton, Dore; Hare, Denise Brown (1993). Noguchi : Due east and Due west. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN0-520-08340-7.

- ^ Gielgud: A Theatrical Life 1904–2000 by Jonathan Croall, Continuum 2001

- ^ Academy of Arts & Letters web site, academicians Archived January 3, 2008, at the Wayback Auto

- ^ AAAS fellows, p. 303 (p.7 of ix).

- ^ Ianco-Starrels, Josine (June 29, 1986). "Noguchi Represents U.S. At 42nd Venice Biennale". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Martha Graham". The Noguchi Museum . Retrieved January two, 2022.

- ^ "Lunar Landscape". The Noguchi Museum . Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ "Lunar Landscape (Woman)". The Noguchi Museum . Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ "Coffee Table". The Noguchi Museum . Retrieved Jan 2, 2022.

- ^ "Noguchi'due south Texas Sculpture · Isamu Noguchi". Texas Sculpture. Fort Worth Public Library. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ "Hiroshima Bridge Railings; Hiroshima, Japan". The Noguchi Museum . Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ "666 5th Artery Ceiling and Waterfall". The Noguchi Museum . Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ "Gardens for UNESCO". The Noguchi Museum . Retrieved January two, 2022.

- ^ "First Lady Melania Trump Unveils Sculpture Installation in the White House Rose Garden". whitehouse.gov . Retrieved November 21, 2020 – via National Archives.

- ^ "Sun". The Noguchi Museum . Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ "Yale Alumni Magazine: Last Look". archives.yalealumnimagazine.com. 2006. Retrieved Dec three, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Sunken Garden for Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library". The Noguchi Museum . Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ "Sunken Garden, Hunt Manhattan Bank Plaza". The Noguchi Museum . Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ "Gardens for IBM Headquarters, Armonk, NY". The Noguchi Museum . Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ "Billy Rose Sculpture Garden". The Noguchi Museum . Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ "Playground for Kodomo No Kuni". The Noguchi Museum . Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ Peggy Guggenheim Collection – Venedig

- ^ "Isamu Noguchi Octetra". Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- ^ "Expo '70 Fountains". The Noguchi Museum . Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ "Twin Sculptures, Bayerische Vereins Depository financial institution, Munich". The Noguchi Museum . Retrieved Jan ii, 2022.

- ^ ""Spirit of the Lima Bean" (1980) by Isamu Noguchi". Public Art in Public Places. June two, 2020. Retrieved June three, 2020.

- ^ Official Biography at the Noguchi Museum website

- ^ "Stamp Series". United States Mail. Archived from the original on August x, 2013. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ^ Noguchi Museum Mission, Vision and Supporters at Noguchi Museum website

- ^ Listing of artists represented at the Artists Rights Social club website Archived January half dozen, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Collectors, artists and lawyers The Economist, November 24, 2012.

- ^ "The Isamu Noguchi Catalogue Raisonné". The Noguchi Museum . Retrieved Jan 2, 2022.

References [edit]

- Noguchi, Isamu (1968). A Sculptor's World . Harper & Row.

- Duus, Masayo; translated past Duus, Peter (2004). The life of Isamu Noguchi: journey without borders . Princeton Academy Press. ISBN0-691-12096-X.

- Kuh, Katherine (1962). The Artist's Voice: Talks with Seventeen Artists . Harper & Row.

- Marika Herskovic, American Abstract Expressionism of the 1950s An Illustrated Survey, (New York School Press, 2003.) ISBN 0-9677994-1-four. p. 254–257

- Marika Herskovic, New York Schoolhouse Abstract Expressionists Artists Choice by Artists, (New York School Press, 2000.) ISBN 0-9677994-0-6. p. 39; p. 270–273

- Lifetime Honors – National Medal of Arts.

- Kenjiro Okazaki, A Place to Coffin Names(about Isamu Noguchi and Shirai Seiichi)

Farther reading [edit]

- Altshuler, Bruce (1995). Isamu Noguchi (Modern Masters). Abbeville Printing, Inc. ISBN 1-55859-755-7.

- Ashton, Dore; Hare, Denise Brown (1993). Noguchi East and West. Academy of California Printing. ISBN 0-520-08340-vii

- Cort, Louise Allison, Bert Winther-Tamaki. Isamu Noguchi and modern Japanese ceramics: a close embrace of the earth, Washington, DC: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003.

- Herrera, Hayden. Listening To Stone: The Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. New York. 2015.

- Lyford, Amy. Isamu Noguchi'due south Modernism: Negotiating Race, Labor, and Nation, 1930–1950 (University of California Press; 2013) 288 pages

- Noguchi, Isamu et al. (1986). Infinite of Akari and Stone. Chronicle Books. ISBN 0-87701-405-1.

- Pina, Leslie (1998). Classic Herman Miller. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing. ISBN0-7643-0471-2.

- Torres, Ana Maria; Williams, Tod (2000). Isamu Noguchi: A Written report of Space. The Monticelli Press. ISBN 1-58093-054-9.

- Winther-Tamaki, Bert. Art in the encounter of nations: Japanese and American artists in the early postwar years. Honolulu: Academy of Hawai'i Press, 2001.

- Weilacher, Udo: "Isamu Noguchi: Space every bit Sculpture", in: Weilacher, Udo (1999): Between Landscape Compages and Land Art, Birkhauser Publisher. ISBN 3-7643-6119-0.

External links [edit]

- The Noguchi Museum

- Official catalogue raisonné

- Official chronology from Isamu Noguchi Foundation

- The Step Gallery

- Noguchi's Indiana experience

- Noguchi'southward California Scenario (LandLiving.com)

- Moerenuma Park (LandLiving.com)

- Artists Rights Society, Noguchi's United states of america Copyright Representatives

- "Noguchi – The Man Who Entered Stone", BigBridge Press, 1999; a biography in poem

- "Isamu Noguchi 'Radio Nurse' Baby Monitor (Annal)". Furniture. Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on December 23, 2012.

- Drawings by Isamu Noguchi from the University of Michigan Museum of Art

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isamu_Noguchi

0 Response to "Being an Artist Who Created Sculpture Gardens Public Art Playgrounds Furniture and Stage Sets"

Enregistrer un commentaire